Mike Foley is Meridian Magazine’s Hawaii correspondent.

If you enjoy Meridian’s inspiring, educational and up-to-minute coverage, please donate to our voluntary subscription drive here. You make all the difference on whether we can bring Meridian home to you.

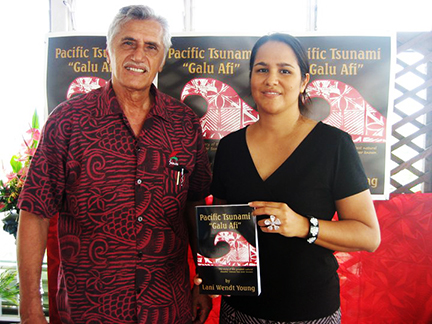

Pacific Tsunami “Galu Afi” is the story of the greatest natural disaster Samoa has ever known, 397 pages, by Lani Wendt Young; edited by Hans Joachim Keil

At 6:48 a.m. on September 29, 2009, an 8.3-magnitude earthquake in the ocean floor about 120 miles southeast of Samoa started the nearby tropical islands to shake, walls to crack and buildings to collapse.

“It felt far more consuming than its one-and-a-half minutes,” one survivor said.

But the earthquake was just the predecessor to a much more destructive galu lolo or tsunami that within about five minutes would strike the three northern-most islands in Tonga, and 10–15 minutes later parts of the islands of Samoa and neighboring American Samoa with deadly force, claiming almost 200 lives.

One grandmother, remembering stories she heard as a little girl about her father’s own boyhood tales of earthquakes and galu lolo, told her daughter and grandchildren to immediately run inland when she felt the shaking. They were saved. Others made similar dashes, but some were caught unprepared in the first surge of the resulting tsunami.

The birds knew, one survivor claimed: “[They] started screeching, it was like a ringing in my ears… I saw them all take off from the trees…but we didn’t have any idea”; and a surfer out early that morning later said, “The sea was bubbling as if a 10-foot-plus wave had just detonated on the reef…millions of gallons of water were creating violent waterfalls.” He wisely paddled farther out to sea and survived.

“We saw the wave coming like fire [or galu afi in Samoan], so we ran”, someone said; but a man in Matautu village added, “It doesn’t matter if you’re a good runner, you’d get caught. The wave was just too fast.”

Some said the wave, starting with the second of four surges, was black; but “the sound of the wave is what most people remember most vividly,” Young wrote — “a rushing wind, or like a train, smashing houses like matchsticks.”

Some drowned quickly while others caught in the surge swam or struggled to safety, but the murky water was filled with “roofing iron that can cut you in pieces, coral boulders torn from the reef, timber beams that will break all your ribs…and you’re in the middle of it.”

Many of those caught in the water who survived suffered “deep, dirty lacerations…cuts and bruises…[and] nasty lung infections.”

Depending on the topography, the waves came across the beach about 10 feet high in relatively level places, but rose to 26 feet in the “tsunami trap” of American Samoa’s Pago Pago harbor and even higher in a few other places. Many climbed trees to escape, including two Mormon missionaries who also helped save a number of young children in their precarious perch. Others scrambled up steep hills to escape.

Some remembered the “ferocity of the wave rather than its height,” Young wrote. In parts of Malaela, a village on the southeastern shore of Upolu island facing the earthquake’s epicenter, “there were no houses left. Only cement foundations with steel inserts gaping through where block walls had been ripped away, as if by a giant hand wiping a slate clean.” Several beachside resorts were particularly devastated, with tourists counted among the injured and dead.

These are just a few of the many incidents Lani Wendt Young compiled in her compelling Pacific Tsunami “Galu Afi”, a book she patterned after David McCullough’s The Johnstown Flood account of that 1889 disaster to “give the reader a sense of ‘really being there.’”

Soon after the event, Hans Joachim “Joe” Keil — a successful Samoan businessman, Associate Minister for Trade and Commerce, and a Latter-day Saint — had commissioned Young “to ensure that a record is kept of people’s tsunami experiences for the benefit of both present and future generations.” They published the book, her first, on the one-year anniversary of the natural disaster that claimed almost 200 lives. The Australian Government Aid Program provided printing funds.

Young, a part-Samoan-Maori mother of five children and a Relief Society teacher in the Pesega 5th Ward in Apia at the time, was born and raised in Samoa but graduated from high school in Washington D.C. when her father — Dr. Felix Wendt, currently Director of LDS Humanitarian Aid and Welfare Services for Samoa and Tonga — was there on a diplomatic posting. She attended Georgetown University and graduated with a degree in English literature and Women’s Studies and a Diploma in Education from Victoria University in Wellington, New Zealand. She was recently released from her Relief Society calling in anticipation of her family moving to New Zealand.

“I consciously made an effort to be ‘church/religion neutral’ throughout the book in terms of identifying the different faiths of survivors interviewed,” Young wrote in an email. “However, members of the LDS church were hit hard by the tsunami and our Church leaders were among the first to respond afterwards.”

In that same email Young pointed out the experiences recounted in the book of three Latter-day Saint families who went through the ordeal were particularly poignant:

Jared and Netta Schwalger, then each 29 years old, had quit their jobs in the capital city of Apia so they could raise their two-year-old son and one-year-old daughter in a more traditional family-oriented lifestyle with his parents in Malaela, which caught the full-on brunt of the tsunami. By the time they realized the earthquake’s portent, they quickly loaded the kids in the family pickup, but it was already too late:

As she turned back to the house to warn her mother-in-law, “the last thing I saw was the wave hit the house and everything was broken in pieces.” The unyielding surge carried the truck into a swamp about 100 yards inland, coming to a half-submerged rest and pinning Netta’s leg. Jared was also hurt but mobile, his father and mother were dead, and “of the children there was no sign.”

As Jared first tried to free her, Netta passed out from the pain. “But when I was out, I heard voices. They were laughing and they were playing. It was my children and I wanted to be with them. But then a voice whispered in my ear to wake up, that it wasn’t my time yet. But I didn’t want to.”

Finally, with the help of others, she was among the first survivors to reach the National Hospital in Apia, where a relief team of doctors from Australia and New Zealand eventually saved her leg from amputation.

Asking relatives to watch her, Jared quickly returned to Malaela where he spent the next three days looking for the body of his son. The little boy and girl were buried about a week after the tsunami, a day before their grandparents’ funeral.

Jared then slept on the hospital floor for the next four weeks while his wife began recovering.

In another seaside village, Leua Viiga reported the tsunami wave washed her and her youngest child into their house, which then collapsed on top of them. She was able to escape when the second surge carried most of the debris away, but her little boy was found dead later that day. Meanwhile, an older son had “grabbed hold of their china cabinet as it swirled past him in the black waters and clambered on top. It would save his life…[though] it should have been destroyed like everything else.” In fact, the dishes inside were intact.

Young wrote that Leua, who spent several weeks in the hospital recovering from a head wound, and her husband are “thankful for tender mercies…[and] have eyes to see miracles”: Unlike many others, her child looked somewhat peaceful in death; the china cabinet is where she and her husband stored their temple clothing, and a family freezer that floated away was later recovered and worked when it was plugged in again.

And in American Samoa, near the southwestern end of Tutuila island, Young discovered that Robert Toelupe — a retired Navy submariner who had been trained in escaping from dark, confusing water — kept going back into the tsunami to save people” while looking for his own missing family members.

For example, he swam and carried one woman to safety, then rescued a boy and his wheelchair-bound father, resuscitated another woman with CPR, and the next day dove repeatedly into a mangrove swamp flooded with foul water to recover the body of a missing girl.

Young wrote that for six weeks after the tsunami, “This little girl kept popping into [Toelupe’s] head,” disturbing his sleep. Later, the girl’s mother gave him “a bundle of papers she had found in a box while cleaning up her tsunami-wracked house…papers that contained vital genealogical information about Toelupe’s family tree and their ancestral rights to a block of land he had been fighting for in court for over 10 years.” They hadn’t realized before that they were related, and he’s since made good progress on his land case. He’s also never seen the little girl again in his dreams.

Young described Toelupe and others as “another kind of hero…[who] in the face of insurmountable obstacles, they still tried desperately to overcome.”

But Toelupe, she continued, disputes people who called him brave for going back into the tsunami. “I didn’t go in because I was brave. I went in because I was afraid. So afraid. Louder than the sound of the waves was the thumping of my heart beating in my chest, and ringing in my ears — that’s how scared I was. I don’t know how to explain the fear I felt, knowing that my daughter and my grandchild were in danger.” They were later found safe.

“I’ve seen people drowning and just remembering what goes on with a person when they’re drowning, that scared me. I felt so scared for my daughter and I felt so scared for everyone in the village,” Toelupe continued. “The fear gets to a point where you’re not worried about safety. I wasn’t prepared to see my children down, the whole time I was praying I wouldn’t see that happen to my daughter.”

Young stressed that people also “continue to comment on the faith and resilience” of all the Samoans and tourists affected by this disaster. For example, a Catholic Church leader in American Samoa “described the book as being a ‘faith filled account’ and I agree. For Church members and non-LDS alike, a common thread with all the survivors was gratitude to God: For sparing their lives, for saving one child (even though two others were killed), for sending them so much help and assistance via generous donors both local and foreign.”

She added that compiling the book also caused her to do a lot of personal soul searching: “Honestly, I would come home from a day of interviewing people and question myself. Could I have been so faithful? So humble? So grateful of my meager blessings if that had been ME who had lost everything?”

* * * * * * *

Pacific Tsunami, which is filled with similar accounts, can be ordered online here at Amazon.com for $39.99 (plus shipping) or in the mainland U.S. at www.keilcreations.com for $35 (includes shipping); in Laie at Cackle Fresh Egg Store, $30, or call Magi Keil at 808-293-5568; and in New Zealand and Australia at https://www.wheelers.co.nz. It is also available at bookstores and other locations in Samoa and American Samoa.