Editor’s Note: Grant Hardy is member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and a professor of History and Religious Studies and the director of the Humanities Program at the University of North Carolina at Ashevile. He was asked to record 36 lectures on sacred texts from around the world. To learn more, click here.

I recently taped thirty-six lectures for the Great Courses (i.e., The Teaching Company) on “Sacred Texts of the World.” There were lectures on the scriptures of Hinduism, Judaism, Buddhism, Confucianism, Daoism, Christianity, and Islam, as well as on the holy writings of smaller traditions such as Zoroastrianism, Jainism, Sikhism, and Baha’i. And yes, there was even a lecture on the sacred texts of Mormonism.

I am sometimes asked why, as a devout Latter-day Saint, I would spend so much time reading other people’s scriptures. After all, don’t we believe that we are part of “the only true and living church upon the face of the whole earth” (D&C 1:30)? And that living by the precepts of the Book of Mormon will bring us “nearer to God . . . than by any other book” (Book of Mormon Introduction)? Why should limited study time be given over to the hundreds of religious texts that could be considered less true or less useful?

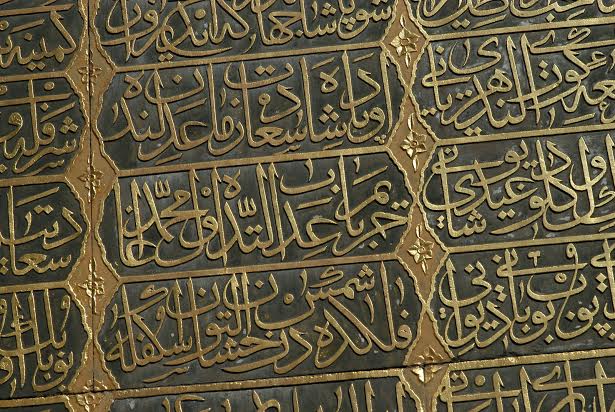

Many of the answers that could be given would apply to believers of other faiths or even to those who don’t believe at all. Religion is very often an integral part of cultural or personal identity. Within your lifetime, you may have opportunities to travel abroad, or to befriend or work with people who are Jewish, Hindu, or Buddhist. You can’t understand the history, or even the present, of China, Japan, and Korea without knowing something about Confucianism and Daoism. And Islam, with its glorious cultural legacy, is central not only to the Middle East, but also to Africa, the Indian subcontinent, and Indonesia (the largest Muslim country in the world).

Showing respect for and knowing the basic beliefs of major religious traditions is an important part of being a global citizen. And having read a little of the Qur’an, or the Lotus Sutra, or the Confucian Analects is a great way to start. In addition, it’s fascinating to contemplate the astonishing variety of religious expression around the world. There appears to be a significant spiritual component to being human, as we might expect from our understanding that all people are children of God.

From a Latter-day Saint perspective, however, my interest goes a little deeper. When I teach religious studies at my secular public university, I always keep in mind two scriptures. The first is the Golden Rule-“Whatsoever ye would that men should do to you, do ye even so to them” (Matt. 7:12)-a principle that can be found in many religious traditions. I think of what my faith means to me and how I would like other people to treat my beliefs, and then I try to reciprocate.

So when I teach a course on the history of Buddhism, I always try to do so in such a way that if one of my students were Buddhist, she would be able to say, “I may not agree with all of Professor Hardy’s conclusions, but I recognize what he’s presenting as my own religious tradition, and he has helped my fellow classmates understand why Buddhism might make sense to those who follow its teachings.” (This has actually happened to me.)

I was nervous about producing a DVD course on world scriptures because I am keenly aware that some people spend their entire lives studying these texts, and I know how annoying it can be as a Mormon when outside “experts” get basic facts about the religion wrong. I worked hard to be as accurate and fair as possible with other people’s scriptures, and I asked colleagues who were Jewish, Muslim, Hindu, and Baha’i to read and critique drafts of my lectures.

Perhaps more pointedly, Latter-day Saints are constantly trying to get their friends and neighbors to read the Book of Mormon. It only seems fair that we should be willing to give serious, respectful attention to their scriptures in return. Indeed, it can be a very useful exercise to try to read something like the Daodejing or the Bhagavad Gita or the Qur’an as an outsider, just to imagine what it might be like to open up First Nephi for the first time and be bewildered by the names, events, and doctrines. And keep in mind that many of those who investigate Mormonism are not coming from a Judeo-Christian background. I am writing this essay in Saigon, a lovely city where we attended sacrament meeting yesterday and heard Vietnamese converts bear testimony of the Book of Mormon. But that volume was once as foreign to them as the Buddhist Pure Land Sutras would be to you.

(Similarly, our family always attends Christmas Eve services at non-Mormon churches. It’s nice to celebrate the birth of our Savior with other Christians, and it’s a good reminder of what it feels like to walk into a church building where you don’t know anyone and are unsure of how the services will proceed. It makes us much more welcoming when new visitors show up at our own sacrament meetings.)

The second scripture I keep in mind when teaching world religions is Alma 29:8: “For behold, the Lord doth grant unto all nations, of their own nation and tongue, to teach his word, yea, in wisdom, all that he seeth fit that they should have.” This suggests that we should be prepared to hear God’s words in languages and texts from around the world, and I don’t mean only in the sense of recognizing truths that we already know from the Restoration. Just because we have “the truth” doesn’t mean that we have all truths. Indeed, we believe that “God will yet reveal many great and important things,” though perhaps he has granted a measure of insight to some of the great teachers of other lands and languages.

I believe that as Latter-day Saints, we can learn religious truths from non-Mormons and even from non-Christians. My spiritual understanding has certainly been enriched by the Confucian notion that we are not autonomous selves, but rather our identity comes from the networks of relationships of which we are a part. I have learned from Daoist insistence that we should live in harmony with nature, from the Buddhist emphasis on compassion and critiques of overly-simple conceptions of the self. I have been inspired by the Jain principle of ahimsa, or non-violence, and the Jewish practice of spirited, intellectually rigorous, faithful debate in the Talmud. And I am deeply admiring of the sort of devotion that leads many Muslims to memorize the entire Qur’an, which is more than half the length of the New Testament.

(Think of memorizing Mathew, Mark, Luke, John, and Acts, word for word. In fact, one of the best introductions to Islam is the 2011 HBO film Koran by Heart, a documentary about three ten-year-olds who travel from Senegal, Tajikistan and the Maldive Islands to Cairo to compete in an annual Qur’anic recitation contest.) In preparing these lectures, I was often moved by the devotion that the faithful of other religions have shown in preserving, studying, and disseminating their sacred texts (often with a level of care that would put Latter-day Saints to shame), and I was inspired to do better myself with the revelations that I believe God has granted to Latter-day prophets.

Mormons like to quote the words of Krister Stendahl, former dean of the Harvard Divinity School and Bishop of Stockholm in the Church of Sweden, which he delivered in a 1985 press conference when he was voicing support for a controversial new LDS temple in that country. At that time, he urged people to leave room for “holy envy,” that is, for finding beauty and meaning in religious practices or beliefs that are not part of their own faith traditions. I have frequently felt that emotion in studying the sacred texts of the world.

Yet I would go a bit further. Even though the basic principles of many religions are, at a fundamental level, irreconcilable, there are nevertheless truths and insights, practical advice and wisdom, from many religions that I would like to adopt-which I feel will make me not only a better person, but also a better Latter-day Saint. According to Alma 29:8, no single nation or tongue has a monopoly on God’s word. God may have a special relationship with the house of Israel, but he loves all of his children; similarly, the Book of Mormon may be God’s special book, revealed for a divine purpose in the latter days, but he has spoken in many times and places to men and women who have sought for greater spiritual understanding.

There is a final reason why I like to learn about other religions: oftentimes this sort of research helps me better understand my own faith tradition. Max Mller, one of the 19th-century founders of religious studies, famously said that “he who knows one, knows none,” meaning that if your study is narrowly focused on a single religion, you will miss a great deal. Let me give you an example of something that I discovered in the process of producing this latest Teaching Company course.

I had done a lecture on the Vedas, the most revered scriptures in Hinduism. These hymns to the gods remained an oral tradition for several thousand years, being transmitted from priest to priest by word of mouth over the course of many generations. Hindu Brahmins resisted putting the Vedas into written form for a very long time because they believed that doing so would make the holy words common and accessible to all. It was important that the Vedas be internalized though memorization, that they were passed on directly from those with proper authority who had already mastered their meanings, and they needed to be spoken aloud, in very specific ritual contexts, in order to actualize their sacred power.

As I was preparing the lecture on Mormon scriptures, it occurred to me that we actually have not four standard works, but five. And the fifth, rather unusually, is oral rather than written scripture; it is the text of the temple ceremony. Look at that last paragraph again and think of how many of those descriptions fit the way that we think about the endowment. The wording of the ceremony is exact and invariable (though the Church has made minor changes from time to time). Most Mormons only encounter these words orally, as the ceremony is performed, and because regular temple attendance is encouraged, many Latter-day Saints have the script memorized. But the words are considered so sacred that we are forbidden from repeating them outside the temple, or even discussing the details of the endowment. Of course, it is possible to find transcripts or even videos of the endowment online, but those cross the boundary into sacrilege. Separated from their ritual context, or in written form, the words lose their significance and become debased.

Who would have thought that Hindus and Mormons have so much in common? And it’s remarkable that in the 21st century, we belong to a religious tradition that includes a deep connection not only to written public scripture, but also to an esoteric, oral sacred text. It really is like an ancient faith transplanted into the modern world.

This realization has also allowed me to see Church history in a new way. Our Restoration scriptures consist almost entirely of revelations to Joseph Smith (aside from three sections of the Doctrine and Covenants and two official declarations), yet the fifth standard work, the endowment ceremony, we owe in large part to Brigham Young. The basic script of the endowment was composed by Brigham, based on an outline and key elements that had been entrusted to him by Joseph. Certainly most Latter-day Saints in the dark days after the martyrdom were introduced to the endowment by Brigham Young as they hastened to perform temple work before they were driven out of Nauvoo. And for the rest of his life, Brigham made the temple and the endowment a priority of his ministry.

So studying the sacred texts of the world has given me a new appreciation for the temple and for Brigham Young. That was not something I could have foreseen when I signed a contract to produce a lecture series, but it’s a small sample of how much we may miss when we ignore other religious traditions and forget that “Lord doth grant unto all nations, of their own nation and tongue, to teach his word.”

To learn more about the lecture series discussed, click here.

beth houkMarch 25, 2014

Thank you for the wonderful insights. I am honored to be your cousin.

LaWren BoothFebruary 28, 2014

Thank you for your thoughtful insights - especially your observation about the temple ceremony. My husband and I once stood in a Hindu temple in New Delhi. In one room there were mirrors on oppostie walls. Our guide explained that the almost infinite reflection which they produced, was to remind us of our eternal nature. Sound familiar?