I recently had the blessing of visiting Norway with my wife. Our whole experience there was invigorating and renewing. However there was one location in particular where I felt the spirit move me to a new awareness.

Oslo’s Vigeland Park stands as one of the world’s most compelling public art installations. At its heart lies the dramatic and deeply symbolic work of Norwegian sculptor Gustav Vigeland (1869-1943), a monumental complex of over 200 sculptures exploring human relationships and life stages. His sculptures reflect a man whose artistic brilliance explores the depths of human emotion while in a constant struggle with his own dissociative nature.

This battle between estrangement and distance was the defining factor in many of Vigeland’s personal relationships, including within his immediate family. He never married, but he did have a long-term relationship with a woman named Laura, with whom he had several children. He was not very involved in their lives, and his children reportedly received little recognition or support from him either financially or emotionally.

His younger brother, Emanuel Vigeland, was also a noted artist, but their relationship was tense and competitive. Emanuel reportedly felt overshadowed by Gustav and even modified the entrance to his own mausoleum so that visitors would bow before his art—a subtle comment on sibling rivalry.

Vigeland was known to be introspective, private, and at times difficult to work with. He had strong opinions about art and life, often clashing with patrons and fellow artists. As a result, he channeled much of his inner conflict and views on the human condition into his work. His sculptures in the park now named after him (an agreement he entered into with the city of Oslo, donating his sculptures in exchange for a studio and financial support) are deeply existential, dealing with birth, death, love, anger, aging, and family—the themes mirroring Vigeland’s own isolation and inner turmoil exacerbated by his mental struggles and family exile.

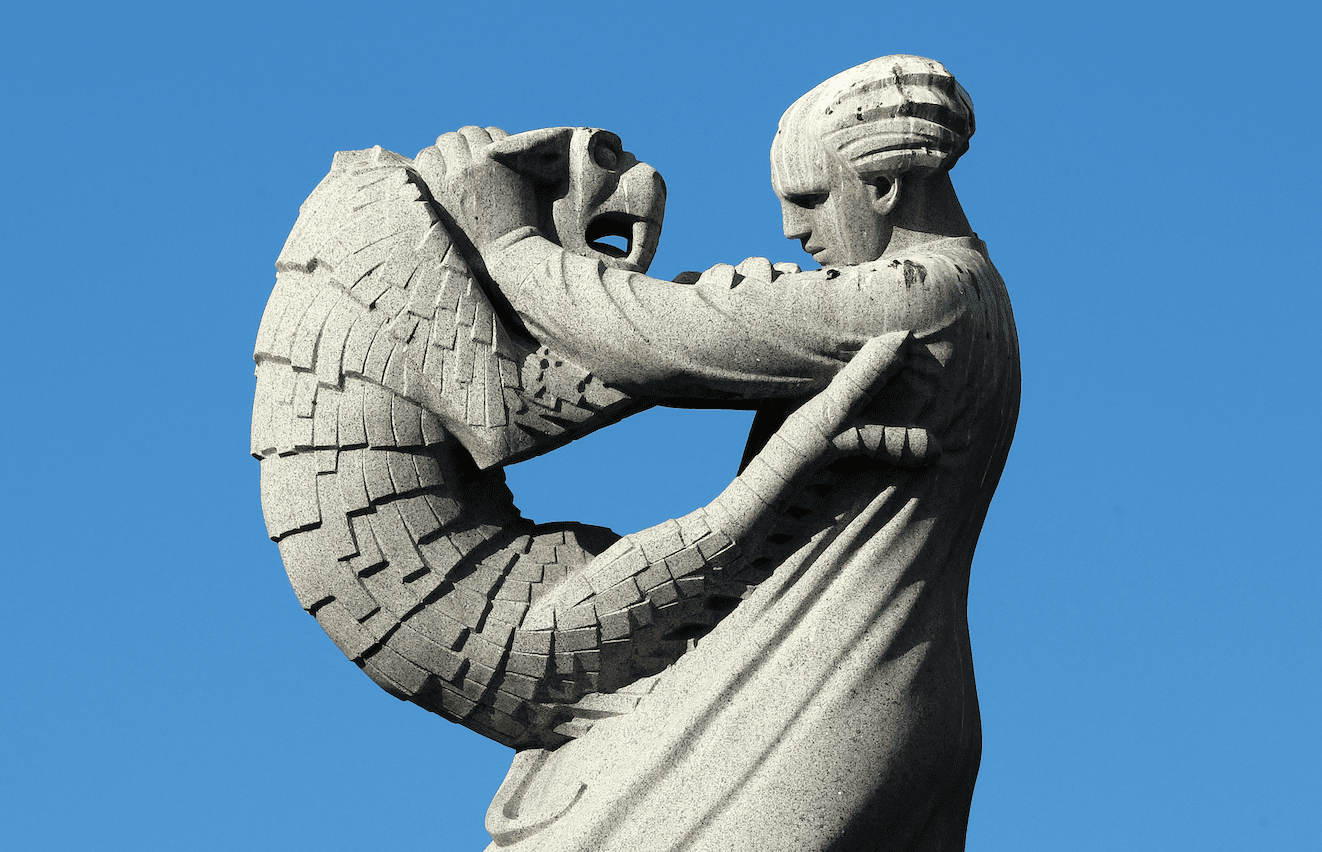

The focal point of the collection is Vigeland’s most imposing work. Known as the Monolith, its 46-foot-high column is carved from a single block of granite displaying 121 human figures entwined in a powerful spiral representing the human lifecycle. However, while impressive, my own emotions were captured by a display of lesser but still striking works, four statues set atop tall pillars—forming the corners of a self-determined square—depicting humans locked in desperate combat with monstrous figures.

These untitled sculptures each evoke a visceral struggle, a primal battle between man and beast that invites interpretation on both psychological and spiritual levels. For members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, these sculptures can be viewed as a visual metaphor for the eternal conflict between the natural man and the divine potential within each soul—a struggle central to the plan of salvation.

Each of these sculptures depict human figures—sometimes single, sometimes multiple—engaged in hand-to-hand combat with monstrous, semi-human creatures. The monsters are grotesque and powerful, sometimes resembling beasts, sometimes more like corrupted versions of the people themselves. These aren’t casual scuffles; they are desperate, life-or-death struggles. The figures twist and strain, caught in poses of tension and resistance, emphasizing the gravity of the battles being fought.

While Vigeland himself did not leave detailed explanations of these works, their symbolism speaks clearly of internal and external battles—of confronting something within or just beyond oneself that must be overcome. For many who see them, these creatures represent fear, addiction, despair, or the darker instincts of human nature. For Latter-day Saints, these sculptures resonate deeply with scriptural teachings on overcoming the natural man, resisting temptation, and striving for exaltation.

Mosiah 3:19 states, For the natural man is an enemy to God, and has been from the fall of Adam. This verse, foundational to Latter-day Saints theology, captures the essence of human spiritual struggle. According to the doctrine, each person is born into a fallen world where mortality brings weakness, pride, and sin. Yet each individual also possesses divine potential as a spirit child of Heavenly Parents. Life becomes a process of choosing—of yielding to the flesh or submitting to the promptings of the Holy Spirit.

Seen in this light, the monstrous figures in Vigeland’s sculptures become symbolic of the natural man—the pride, anger, lust, fear, and despair that must be conquered in order to become more Christlike. The physicality of the struggle in the statues mirrors the daily spiritual discipline required of the Saints. It is not a one-time battle but a continual effort, requiring grace, agency, and persistence.

An important nuance in Latter-day Saint doctrine is the belief that while each person must strive to overcome sin, it is only through the Atonement of Jesus Christ that true transformation is possible. As 2 Nephi 2:8 teaches, …there is no flesh that can dwell in the presence of God, save it be through the merits, and mercy, and grace of the Holy Messiah. Thus, while the sculptures show individuals wrestling alone, Latter-day Saints understand they are not alone in their struggles as the power to ultimately overcome the monster comes through the enabling strength of the Savior’s Atonement.

These stone warriors represent a mortal moment—where the struggle is ongoing and the outcome uncertain. But Latter-day Saint teachings provide hope and assurances that through Christ, the monster can be subdued. This hope is echoed in Ether 12:27, where the Lord promises to make weak things become strong, And if men come unto me I will show unto them their weakness… then will I make weak things become strong unto them.

In Latter-day Saint theology, opposition is not only expected—it is essential. As Lehi explains in 2 Nephi 2:11, …it must needs be, that there is an opposition in all things. Struggle refines the soul, teaches humility, and invites individuals to turn to God. The figures in Vigeland’s sculptures are not portrayed as villains or sinners; rather, they are heroic in their efforts to resist the beasts. Their very struggle affirms their worth.

This connects closely with the Latter-day Saint view that life is a testing ground, where agency is exercised and character is formed. Far from being condemned for having monsters to fight, Latter-day Saints are taught to see such struggles as the proving ground of discipleship. The goal is not perfection in this life, but faithful striving, trusting in Christ to make up the difference.

Gustav Vigeland, whether consciously or not, created in these four pillar sculptures a profound visual representation of the universal human condition. For Latter-day Saints, they stand as stone witnesses of an eternal truth—that every soul must confront darkness, both within and without, and that victory is possible only through divine help. Though made of granite, these figures point to something deeply spiritual—a reminder that our own monstrous challenges are not signs of failure, but invitations to grow, to reach upward, and ultimately to be transformed through Christ.

In the shadow of these statues, one might remember Moroni’s invitation, Come unto Christ, and be perfected in him (Moroni 10:32). The battle is real—but so is the hope.