![]()

By Rose Datoc Dall

Jacqui Larsen, BACKYARD COSMOLOGY, oil on canvas with salesman’s sample screen door, 70″ x 100,” 1999.

(Image Courtesy of BYU Museum of Art)

Pioneering Exhibition

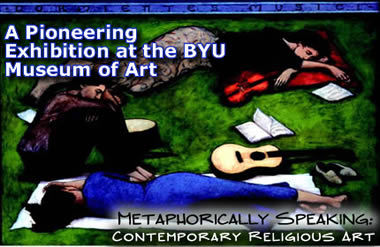

When one thinks of the word “pioneering” in an LDS context, images of early LDS pioneers crossing the plains come to mind. But “pioneering” takes on a new meaning when referring to an exhibition which opened in April at the BYU Museum of Art and which will be on display until January of 2005: The exciting exhibition is entitled Metaphorically Speaking: Contemporary Religious Art, an exhibition featuring the work of 12 contemporary artists who are Latter-day Saints from around the country.

The artists are installation artists and sculptors Galen Bell Smith, Mandi Mauldin Felici and Carin Fausett: mixed-media artist, Jacqui Biggs Larsen; painters David Linn, Brian Kershisnik, Ron Richmond and Sean Diediker, designer David Hoeft; printmaker Ashley Knudsen; fiber artist Becky Knudsen and husband and object artist/primitive artist Kurt Knudsen. Of the group, 8 out of the 12 are BYU alumni, all of which have either a Bachelors or Masters Degree in Fine Art.

“Nothing like it has been done before,” at the BYU Museum of Art, says Museum curator Dawn Pheysey, largely due to the vision of BYU Museum Director Campbell Gray. On exhibition is a type of religious art that perhaps LDS audiences are unaccustomed to viewing by a collective of artists who are LDS.

To view the online exhibition, visit https://cfac.byu.edu/moa/

Opening Reception, April 8th at the BYU Museum of Art

(Image Courtesy of BYU Museum of Art)

Non-Narrative Contemporary Religious Art

None of the art in this exhibition is strictly narrative or, in other words, where a very specific story is told and all the work-is-done-for-the-viewer, or where, viola, we as viewers are left only to simply behold. But rather, the art in this exhibition is an exploration into the spiritual through the use of symbol and metaphor; its very object is to use subliminal imagery in an unexpected way to challenge the viewer and involve mental participation.

By our very nature, we as viewers have a tendency and desire to find something recognizable in the images that we are viewing. The natural inclination is to find a story or narrative. These artists purposefully avoid literalness and make use of visual metaphors. We then as viewers are enticed to participate by making our own connections based on our own personal archive of experience to find meaning.

One of the participating artists Galen Bell Smith says, “I am not just interested in making pretty pictures.” She further states that she has a strong desire not to be associated as a narrative genre artist, a similar sentiment held by most of the artists in the exhibition. Once having done figurative illustration, Smith now rarely ever incorporates the figure directly into her work. Rather her sculptural objects of books as in Book of Feast and Nail Series make reference to those religious symbols which are familiar to us as Latter-day Saints.

(Image Courtesy of BYU Museum of Art)

Imagery in Contemporary Art

Symbol and imagery has been used for centuries in literature and in art for centuries. But in the visual arts, the use of imagery, content-driven or narrative art had been abandoned and dismissed for a good part of the twentieth century to give way to abstraction by the purists and the formalists. Representational art by the late 19th century had lost its credibility in terms of inventiveness; after its height, anything representational that followed would have been viewed as a dishonest copycat, a mindless replication, or a rehash.

Consequently, twentieth century art became about the exploration of inventive expression with its root in abstraction. But after the abstraction in its extremes, its sub-forms and spin-offs ran its full course during the twentieth century, the natural pendulum began to swing back in the latter part of the twentieth century when it finally became kosher for traditional elements and imagery to reemerge from its dormancy in the artistic library, ready to be reinvented, reutilized and referenced as vehicles in contemporary art.

It is not surprising then, that many artists who are Latter-day Saints, many of whom keep a close tether to or have had their training in traditionalism, figurative and representational art have found a voice in contemporary art and jumped on board; yet having inherited the lessons of the twentieth century art, they have incorporated some of those artistic sensibilities and contemporary methods of expression which had been in full swing by the end of the last century.

(Image Courtesy of BYU Museum of Art)

Contemporary expression includes but is not limited to experimentation, odd juxtaposition, eclecticism, object art, non-literalness, scale and manipulation of space as a vehicle, ephemeral and installation art, use of mixed media and unexpected media, unconventional presentation, outside-the-box mentality, anything-goes attitude, tongue-and-cheek humor, whimsy and primitivism. For the contemporary artists in this exhibition, the full gamut has become the vehicle for expression whose main inspiration is rooted in their testimonies, their religious and spiritual beliefs: thus, contemporary religious art.

(Image Courtesy of BYU Museum of Art)

(Image Courtesy of BYU Museum of Art)

It definitely is refreshing to see artists of this kind of art emerging from a body of artists who are Latter-day Saints. Many of these artists are also gaining recognition and there are many more artists out there who still live in obscurity that are producing work along similar lines. This exhibition only shows the works of 12 artists.

“I loved the show… to see a lot of other [contemporary] artists who are making spiritual art and are successful,” says participating artist Mandi Mauldin Felici, whose large nest-like installation pieces like Haven are statements about “home” and even evoke a reference, whether intentional or not, perhaps to the manger. The beauty of metaphor is in its intentional ambiguity: it is completely unscripted and left for the viewer to draw his/her own conclusions about what he/she sees or feels.

To view the online exhibition, visit https://cfac.byu.edu/moa/

Distinction from Other Contemporary Art

While the religious art in this exhibition fits and functions in that realm of contemporary art, which should appease the “artist’s artist,” so to speak, as well as the intellectual, sophisticated viewer, the art created by this group of artists definitely holds one distinction from contemporary art in the world: it has none of the darker qualities which can pervade contemporary art, nor is it motivated by any of these elements, such as cynicism, suspicion, social or political spite, assault on public sensibility, need to shock, mockery of institutions, alienation, explorations into self-indulgence or the dark tendencies of human nature, promotion of alternate lifestyles and destructive subcultures, degradation of the human body, and profanity of the sacred as a vehicle.

(Image Courtesy of BYU Museum of Art)

Such methods and statements “would be antithetical to the Gospel of Jesus Christ,” says artist David Linn whose large oil panels of broad and almost surreal landscapes and seascapes pull the viewer into his world where the path becomes the metaphor; for himself it is a homage to his own pioneer heritage, and in the larger sense the path is also a metaphor of the perilous road that anyone must take to “follow the Savior,” as in the Imminent Event.

(Image Courtesy of BYU Museum of Art)

“Hope is a big part of what my work is about,” says Jacqui Larsen, whose multi-media collages such as Backyard Cosmology or And Leona make analogies to the journey through life and a “look to the future. [a] look to our Savior.” Jacqui states, “I am interested in a personal art.that can uplift me.” “People are receptive to work that has humanity in it.”

To view the online exhibition, visit https://cfac.byu.edu/moa/

The Challenge of Contemporary Art in an LDS Culture

The path of a contemporary religious artist is not an easy one for a Latter-day Saint, in terms of gaining recognition and acknowledgement in the LDS culture. The artists in this exhibition, with the exception of a few, have been operating outside the greater LDS culture’s awareness that this type of art was being produced by artist in the Church.

Most of the art is not commercially driven, nor is its primary intent to be reproduced for popular dissemination. Certainly individual artists have been doing work of this kind and have been for some time, but were it not for an exhibition at the BYU Museum of Art, this group might not have enjoyed the impact that this exhibition has to impress upon the LDS public that “here we are and this is what we are all about.”

Secondly, these artists might have felt a lack of understanding by their own LDS culture which is more accustomed to and very comfortable with narrative artwork. Historically and culturally, Latter-day Saints have always been a very practical people who respond to “functionality.” For instance, narrative art holds a very distinct role in terms of its functionality: it illustrates and teaches very specific events or principles with directness.

The LDS culture is not necessarily very comfortable with non-narrative art and contemporary expression, however, in understanding its own relevance in its own culture. Certainly, members of this church in this very sophisticated society have seen art of this kind in museums and galleries dotting this country and the world. But Latter-day Saints, perhaps, are not used to seeing contemporary art in an LDS context, and therefore, simply don’t know what to do with it, nor what to make of it.

For the most part the education and exposure to contemporary art principles to this day remains very confined and relegated to more specialized art institutions and remains lacking in the larger cultural diet of the average Latter-day Saint and is therefore dismissed and often overlooked all together. This exhibition’s intent is to educate the public and begin the dialogue amongst its largely LDS student body and populous.

“This show may leave some people scratching their heads,” says artist Brian Kershisnik in full acknowledgement that while the art entices the viewer to participate, it does not demand understanding by all who view it, but it can evoke different meaning to different individuals.

The non-narrative work in this exhibition functions more like parables, meant to speak to individuals on many different levels, while completely washing over some all together. In the introductory panel for the exhibition, it states:

“As believers in Christ we are somewhat adept at deciphering the literary symbolism-parables, similes, metaphors, allegories, and signs-found in the scriptures. But we tend to be less comfortable with interpreting works of art that use symbolism to represent religious truths. Such interpretation requires thoughtful time and effort in order to comprehend the visual signs and emblems that can play such a critical role in our definition and understanding of spiritual values and beliefs.

Perhaps it was BYU Museum Director Campbell Gray’s intention to validate religious contemporary art’s relevance in our current LDS culture. The bottom line is that contemporary religious art is not going away, and many more artists who are Latter-day Saints are creating along similar lines and are emerging. Therefore, we can expect to see more contemporary art like it in the future produced by the LDS culture. The brilliancy lies in Gray’s grasp of the beat of contemporary culture in relation to LDS culture, addressing its cultural reckoning and even anticipating the direction that art may evolve in the Church.

(Image Courtesy of BYU Museum of Art)

To view the online exhibition, visit https://cfac.byu.edu/moa/

The Challenge for the Religious Contemporary Artist in the Contemporary World

Another challenge for any artist who is LDS lies in the temptation to follow the world; there are disparate ideologies that exist between the art world and the doctrine of Christ. But the “perception” of a lack of application of contemporary art in LDS culture may alienate and drive many contemporary LDS artists to seek acceptance outside their own culture. Seeking credibility as an artist in the art world can present a potentially dangerous moral dilemma when so much attached to that life-style can be antithetical to gospel values and may demand the artist to compromise morals at one point or another.

After all, the world view is that the artist creates-his/her-own “moral universe.” To vocalize one’s values or sense of morality has rarely ever been “chic” in art circles and certainly can lead to a backlash amongst artistic peers because it “implies” or comes off as narrow-mindedness and limitation- it goes against the artist’s “moral-universe” ideology.

The artists in this exhibition are fully aware of the dilemma, but each have their own way of dealing with it.

“For me it is a self-inflicted dilemma,” says Galen Bell Smith.

In great humor, Brian Kershisnik’s favorite motto is “we are the artists and we have failed,” meaning that artists have been “unreliable” over the centuries in their responsibility of handling wisely the gift and powerful tool of art. In Kershisnik’s admiration for masters Matisse and Picasso, his knowledge of the gospel prevents him from following the lifestyle of the stereotypical artist where the artist is at the center of his/her own “moral universe” devoid of responsibility. Some of the greatest artists who have led extreme lifestyles have been some of the most ill-adjusted and self-destructive individuals, such as brilliant and revolutionary architect, Frank Lloyd Wright and influential pop-artist Andy Warhol to only name two.

Kershisnik, whose paintings and publications have attracted attention, is also scheduled to exhibit in a gallery in Soho, New York, a significant coup for any artist. His figurative paintings are an introspective study that acknowledges “the difficulty and awkwardness and inscrutability of life.but [that] there is optimism.” Dormientes Musici (Sleeping Musicians) is about a statement of the struggles of the artist who so often lives an unbalanced life of imbalance.

(Sleeping Musicians), oil on canvas, 94″ x 113.5,” 2001.

(Image Courtesy of BYU Museum of Art)

“There should always be something more important than art,” says Brian Kershisnik, when discussing balance in the life of an artist. Brian happily proclaims thankfully that he teaches in the Primary. Brian, who wakes up every morning and goes to his studio and begins his day in prayer, says, “We just need to be good.”

“There is room for spiritual art in the higher art world [to be] taken seriously. [There is] an important place for this type of art, [addressing] contemporary issues and [using] contemporary methods but expressing faith through the methods,” says Galen Bell Smith.

“There is room for everything,” says Jacqui Larsen and as far as any religious art where “there is a sense that the individual is a divine individual. there will always be an audience for that [amongst] viewers and collectors and dealers.”

“I’ve never encountered any struggle in reconciling [this issue], says David Linn. “The gospel is all encompassing in its doctrine… very embracing of truth.”

Conclusion

The irony to the world view is that within in the Gospel of Jesus Christ there is universality in truth, and that truth can take shape in all forms of expression by artists everywhere, as opposed to the artist’s own “moral-universe” theory which distorts this truth and promotes a misunderstanding of this principle. There is room for all kinds of art and definitely room to appreciate contemporary art, even by LDS audiences, especially that which is created by its own culture.

Bravo to these contemporary religious artists for their participation in a stunning and thought provoking show. The quality of its presentation rivals the best in any contemporary gallery or museum, another hallmark of the BYU Museum and its design team which bring a sense of world-class art to its public and to the university. And bravo to Museum Director Campbell Gray and Curator Dawn Pheysey for having the vision to present this pioneering exhibition at the BYU Museum of Art. It certainly opens the door for other Latter-day Saint contemporary artists in their struggle to find a voice. We hope to see more exhibitions like it in the future. We highly recommend a visit to the BYU Museum before the exhibition closes in January of 2005.

To view the online exhibition, visit https://cfac.byu.edu/moa/