During Wilford Woodruff’s ten-year administration as President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, he and his counselors in the First Presidency issued many mission calls. In turn, these men responded by letter to explain whether or not they could accept the call to serve. Although one might assume that their responses would be rather businesslike and uninteresting, they are actually full of vivid details about the lives of nineteenth-century Latter-day Saints and how their mission calls impacted their lives. These men faced various obstacles to missionary service, and the letters explained their circumstances as well as some of the special requests made to help mitigate their challenges. A close study of just 135 of the responses written to Wilford Woodruff in 1889 allows for a greater appreciation for the sacrifices and faith of those called to serve missions during this time.

The Unpredictability of Life in 1889

The 135 correspondents were very diverse in terms of age, economic status, and location and they responded in a variety of ways to the call to missionary service. Some accepted the call with a simple, straightforward “yes,” committing to be ready to leave on their assigned departure dates to their assigned areas.1 Others, who also accepted mission calls, phrased their acceptance in a much more tentative and qualified way. For example, George Jex wrote: “I will try and be on hand at that time, knowing nothing to prevent me at present, hoping that there will be nothing.”2 James Horne similarly said: “If nothing happens more than I know of, I will try and be on hand at the time appointed.”3 A Brother Dahlquist went further than this, saying, “I will try to be on hand ready to start on the date named in your letter, but if it shall be found that I could not straighten up my affairs by that time . . . I suppose you would grant me a short extension of time . . . [but] I will do my uttermost to get ready . . . on the day above named.”4

At first glance the hesitant tone in these letters might give the impression these men lacked the commitment and desire to obey the call to missionary service. However, these responses reflect how unstable and unpredictable their lives were, more than a lack of faith. Frontier life in 1889 was often challenging and unpredictable. In spite of all one’s work and effort, an early freeze or bad storm could destroy the harvest. An unexpected work accident could leave a farmer seriously injured. Severe illness, which was frequent, could devastate struggling families.

Most likely, these men were just being realistic when they gave such tentative responses. This is clearly illustrated by the experiences of Hans Eriksen, who initially responded to his mission call declaring, “I will do all in my power to be ready till the date named in your letter, as far as my circumstances will allow.”5 Then, four months later, he wrote back saying “I have done all in my power . . . but I am not able to get enough money,” and he asked to have his departure date postponed for a month.6 Their hesitant but willing responses may often have been the best answers they could give.

Other letter writers told the First Presidency right from the start that, although they were willing to go, they would need extra time to get ready. One of the most common reasons why missionaries requested a later departure was financial difficulty, often unpaid debt. Many other challenges also led missionaries to request more time to prepare. Brigham Johnson explained that he needed to resolve “a [legal] contest against my farm which no other but myself can attend.”7 Ten days before his own departure date, Antoine Hopfenbeck communicated to the First Presidency that he had been “quite sick” for almost four months and would need more time to recover.8 Charles Gledhill wrote that his wife had recently died, that there was no one to watch his house in his absence.9

Another letter writer was not able to immediately begin Church service as a missionary because he was already preoccupied with Church service at home. Bishop John Clarke said that he was willing to go on a mission but needed time to settle the ward’s tithing accounts with the stake, find someone else to run the local cooperative mercantile store for him, and prepare his ward for his absence.10 While Bishop Clarke was willing to be both a bishop and a missionary at the same time, another bishop was not so sure. Bishop John Booth of Provo wrote the First Presidency: “I notice that matters in the ward suffer when I am away and are likely to except someone else should be appointed to the Bishopric.”11 He was willing to serve but was concerned that if he had two Church positions, he would not be able to fulfill both adequately.

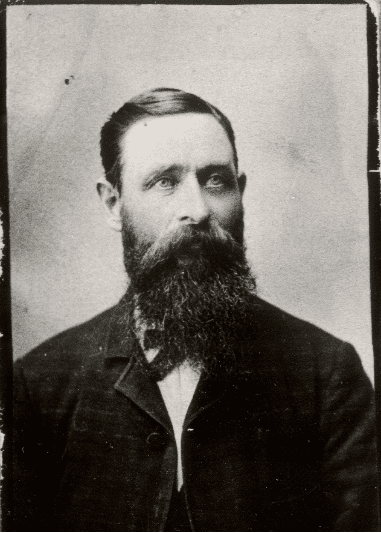

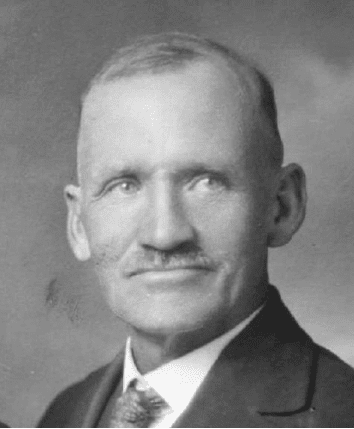

John H. Clarke John E. Booth

Others sought to delay or decline mission calls because their efforts at home were making the missionary service of others possible. Hans Jensen asked to have his mission postponed for a year, because he was looking after the property of a Brother Andersen who was serving a mission (and who would return the favor when Hans went on his own mission). Hans also explained that he had taken upon himself the “debt of one of the Elders that had left this place for a missionary field,” which he was still working to pay off. Far from being uninvolved in missionary work, Hans’s everyday efforts were making it possible for at least two of his neighbors to preach the gospel.12

Although many men wanted a delayed departure date, it was extremely rare for someone to actually turn down a mission call. Out of the 135 men, only six asked to be excused from service and two of them cited serious health conditions.13 The fact that almost all agreed to serve demonstrates their religious devotion: they were willing to make great sacrifices and overcome difficult circumstances to obey a call from God to serve.

The Impact of Federal Anti-Polygamy Prosecution on Missionary Service

Of course, most of the obstacles to serving a mission, like debt, illness, and family need, were not unique to the late 1880s or even to Wilford Woodruff’s presidency as a whole. These difficulties have affected many considering missionary service, both before and after 1889. However, one issue that was unique to the 1880s was the federal government’s intensive campaign to end the Latter-day Saint practice of plural marriage. Throughout this decade, government forces doggedly worked to implement anti-polygamy laws by prosecuting and imprisoning Latter-day Saint men throughout the Western United States. This led many men and their families to go into hiding, or “on the underground.” Anti-polygamy prosecution was reaching a climax in 1889—just one year before President Wilford Woodruff would issue his famous Manifesto that began the process of ending plural marriage.

Hans Eriksen

Something that so deeply affected the Latter-day Saint people would impact the decision of whether or not to serve a mission. Hans Eriksen’s letter to Wilford Woodruff reflects the tension and fear of the times. He wrote: “I was arrested last year but as there was no evidence the case was dismissed, but I am in danger every day of being arrested and charged with adultery.” He accepted his mission call, declaring: “I would rather go to Scandinavia than the penitentiary, as I hope I can do more good there.”14

However, going on a mission was only a temporary reprieve from the persecution, as a letter from Bryant and Lewis Hawkes shows. These two brothers explained that their father had “recently returned from a mission in the Southern States and has since served a term in the Idaho Penitentiary of five months.”15 Once his mission ended, the federal marshals were still waiting.

Lennert de Lange

The federal anti-polygamy raids also affected entire communities. When Leonard de Lange wrote a letter to President Woodruff requesting more time to prepare for his mission, it was Peter Olsen, a counselor in the bishopric, who endorsed his letter because the bishop was in hiding on the underground. In fact, according to Brother Olsen, “many of our Brethren here are in exile, one in the penitentiary, and two more going there before long.” The absence of so many men was making it hard for the ward to function, and Brother Olsen reasoned that Leonard de Lange would “be of great service to the ward under the present circumstances” and asked for the mission call to be delayed by a year.16

Around this same time, Latter-day Saints in Idaho were facing a particularly unusual challenge. All Latter-day Saints there had had their voting rights taken away because of the Church’s doctrine of plural marriage. In October 1888, in order to work around what they believed to be an unjust situation, some Church leaders briefly endorsed the practice of Church members resigning their Church membership during the election, then having their membership reinstated after the election. Leaders quickly changed their minds and began discouraging this practice, but hundreds of Latter-day Saints had already temporarily resigned their Church membership in Idaho.17

John Maughan was one of the Latter-day Saints in this awkward and difficult situation in early 1889, which impeded his ability to serve a mission. Writing on behalf of Brother Maughan, Bishop John Clarke of Weston, Idaho, said: “Bro[ther] Maughan is one, among the many, who resigned his position in the church, for the cause of political liberty in Idaho. He, as well as many others, are watched closely by our Enemies, and cannot under present circumstances accept of the mission. He is willing and would be glad to go, and thinks that in the near future, there will be a change, when he will be at liberty to accept.”18

Church members and leaders were under extreme pressure as the anti-polygamy campaign came to its breaking point in the final year before the Manifesto was issued in 1890. The responses to mission calls in 1889 show how the anti-polygamy efforts affected the ability to spread the gospel throughout the world.

Requests to Serve in Specific Locations

Missionaries occasionally made requests to serve in specific locations. While missionaries themselves typically made these requests, in one case, it was the mother of a missionary who asked. Anna Hellstrom of Colonia Juarez, Mexico, wrote the First Presidency, saying she had heard that her son John who lived in Richfield, Utah had been called on a mission to Europe. She informed them that John’s wife had just died in childbirth, leaving him with three small children and no relatives nearby to help care for them. So she proposed, “If it is not asking too much, could his mission be changed from Europe to Mexico and he be appointed to . . . help build up the settlements of the Saints in this land.” She said that she could watch his children while he could help her in her old age with her farm work, arguing that this would “thus assist him and me in helping each other.”19

John Hellstrom

Although this seemed like a great idea to Anna, it did not sound so good to John, who apparently had not been consulted first and was very surprised to hear what his mother had done. After the First Presidency sent John a “kind letter” asking about his situation, he wrote back: “I hasten to reply. Will say that my good old mother no doubt feels interested in my welfare, but . . . my wife’s parents and relatives reside here [in Richfield] and are willing to care for my little ones during my absence into the missionary field . . . I do not care nor wish to go to Mexico or anywhere else in particular, except as before stated, only where the Lord through his servants want me.”20

Most often, if missionaries asked to serve in a specific location, they requested to be sent to their family’s place of origin so they could gather genealogical records.21 This was actually the case with John Hellstrom who was looking forward to serving in Sweden so he could gather information on his ancestors. John and others like him saw this as an expansion of their missionary service, sharing the gospel on both sides of the veil.

Willingness to Sacrifice for a Mission Call

Despite their hardships and difficult conditions, these faithful men were still willing to prepare themselves to serve when they were called and where they were called. For example, Gottfried Eschler wrote: “If I look at it naturally, it looks almost impossible for me to leave my family the way I have to leave them. But I will do according to your request and would not for anything disobey your council.”22 It is striking that so many of these men said they were willing to obey their leaders even if it meant doing something that seemed practically impossible. Some may have accepted out of respect for their leaders. However, others sincerely meant that they would make any sacrifice in order to fulfill a divine calling from God.

Oliver Cowdery Dunford

The level to which some were willing to sacrifice for God’s work is dramatically demonstrated by a letter written by Oliver Cowdery Dunford. Oliver received a mission call to New Zealand just eight days before he was planning on traveling to the University of Michigan to study law. He explained to President Woodruff that this was “the great desire of [his] heart” and that he had “been planning for the accomplishment of this for several years.” Now that he had “succeeded, finally, in surmounting every apparent obstacle of any consequence,” he had received his mission call. Nevertheless, he declared: “I feel like sacrificing all of these fond anticipations, that have given me much pleasure of late; and subjecting myself to the will of my Heavenly Father, firmly believing that all will be well in the future.”23

He did not ask for a reprieve but committed to obey the call he had been given. True to his word, Oliver left with his wife, Ida, on a three-year mission to New Zealand and, when they returned, “multiplied burdens of family life and debt” kept Oliver from ever going to law school.24 Men like Oliver wanted to show faith and obedience to God no matter the cost, because their faith in Him was worth more than even their most fervent dreams and personal desires.

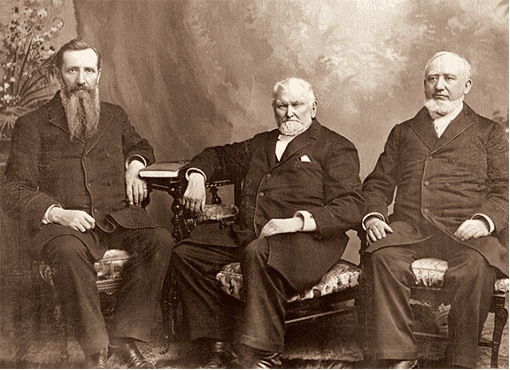

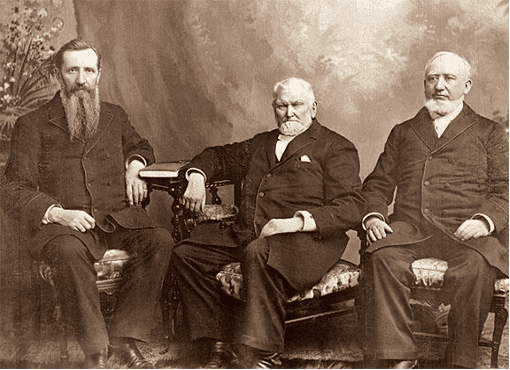

Wilford Woodruff and his counselors

President Wilford Woodruff and his counselors showed great respect for the concerns and requests of those that were sacrificing so much and granted every request that these men made to them. Regularly included marginal notes written by the First Presidency’s office, with comments like “give him time,”25 and “take the time necessary.”26 Church leaders were calling men who had not completed a missionary application, as young missionaries and senior couples do today. They weren’t necessarily expecting a call and many had families to provide for and livelihoods to maintain. So, by understanding and being willing to work with the unexpected, the First Presidency increased the likelihood that people could actually fulfill the calls to serve.

President Woodruff and his counselors recognized and appreciated the difficult sacrifices they were asking these men and their families to make. As a former missionary himself, President Woodruff would certainly have understood well the challenges and would have empathized with them. The responses to these calls to serve teach us a lot about the dedication, faith, and self-sacrifice that nineteenth-century Latter-day Saint missionaries demonstrated, in spite of the varied challenges and obstacles they were facing. They left a great legacy of dedication and faith that can inspire today’s Latter-day Saint missionaries as they accept their own calls to serve with faith knowing that God will sustain them as they share message of the restored gospel with the world.

Hovan Lawton is originally from Provo, Utah, and graduated in 2021 from Brigham Young University with a Bachelor of Arts in history. He is currently finishing a master’s degree in history at Utah State University, where he holds the Arrington Fellowship. His research interests include nineteenth-century Latter-day Saint history in the American West, as well as the history and development of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Latin America.

Hovan received the Carol Sorensen Smith Award and was selected to present his exemplary research at the Wilford Woodruff Papers Building Latter Day Conference in March 2023.

The Wilford Woodruff Papers Project’s mission is to digitally preserve and publish Wilford Woodruff’s eyewitness account of the Restoration of the gospel of Jesus Christ from 1833 to 1898. It seeks to make Wilford Woodruff’s records universally accessible to inspire all people, especially the rising generation, to study and to increase their faith in Jesus Christ. See wilfordwoodruffpapers.org.

Endnotes

Some text from the historical documents has been edited for clarity and readability.

1 See, for example, Letter from Wilford Woodruff Clark, April 25, 1889, p. 1, The Wilford Woodruff Papers, wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/letter/1889-04-25.

2 Letter from George H. Jex, January 6, 1889, p. 1, The Wilford Woodruff Papers, wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/letter/1889-01-06.

3 Letter from James M. Horne, September 6, 1889, p. 1, The Wilford Woodruff Papers, wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/letter/1889-09-06.

4 Letter from L. Dahlquist, February 25, 1889, p. 1, The Wilford Woodruff Papers, wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/letter/1889-02-25. Italics added.

5 Letter from Hans Eriksen, May 31, 1889, p. 1, The Wilford Woodruff Papers, wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/letter/1889-05-31.

6 Letter from Hans Eriksen, September 26, 1889, p. 1, The Wilford Woodruff Papers, wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/letter/1889-09-26.

7 Letter from Brigham M. Johnson, December 16, 1889, p. 1, The Wilford Woodruff Papers, wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/letter/1889-12-16.

8 Letter from Robert Campbell written on behalf of Antoine Hopfenbeck, March 30, 1889, p. 1, The Wilford Woodruff Papers, wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/letter/1889-03-30.

9 Letter from Charles Gledhill, August 20, 1889, p. 1, The Wilford Woodruff Papers, wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/letter/1889-08-20.

10 Letter from John Henry Clarke, June 13, 1889, p. 1, The Wilford Woodruff Papers, wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/letter/1889-06-13.

11 Letter from John E. Booth, June 12, 1889, p. 2, The Wilford Woodruff Papers, wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/letter/1889-06-12.

12 Letter from Hans Jensen, January 10, 1889, pp. 1–2, The Wilford Woodruff Papers, wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/letter/1889-01-10.

13 Letter from Lewis Peter Johnson, February 13, 1889, The Wilford Woodruff Papers, wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/letter/1889-02-13; Letter from F. S. Fernstrom, June 14, 1889, wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/letter/1889-06-14; Letter from M. Forster, September 1, 1889, wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/letter/1889-09-01; Letter from Matthias F. Cowley, June 14, 1889, wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/letter/1889-06-14; Letter from John Jardine, March 9, 1889, wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/letter/1889-03-09; Letter from Henry Hendrickson, March 5, 1889, wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/letter/1889-03-05.

14 Letter from Hans Eriksen, May 31, 1889, pp. 1–2, The Wilford Woodruff Papers, wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/letter/1889-05-31.

15 Letter from Bryant and Lewis Hawkes, September 17, 1889, p. 1, The Wilford Woodruff Papers, wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/letter/1889-09-17.

16 Letter from Leonard G. de Lange, March 11, 1889, pp. 1–2, The Wilford Woodruff Papers, wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/letter/1889-03-11.

17 John S. Dinger, “Resigned to Fate or Resigning to Vote: The Idaho Test Oath and Woolley v. Watkins,” Journal of Mormon History 46, no. 4 (October 2020): 60–61, 74–89.

18 Letter from John H. Clarke, February 9, 1889, p. 1, The Wilford Woodruff Papers, wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/letter/1889-02-09.

19 Letter from Anna B. Hellstrom, March 14, 1889, First Presidency missionary calls and recommendations, 1877–1918, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, UT, ChurchofJesusChrist.org/letter/1889-03-14.

20 Letter from John A. Hellstrom to George Reynolds, April 15, 1889, First Presidency missionary calls and recommendations, 1877–1918, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, UT, ChurchofJesusChrist.org/letter/1889-04-15.

21 See letter from John A. Hellstrom, April 15, 1889; see also letter from Canute Peterson, February 26, 1889, p. 1, The Wilford Woodruff Papers, wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/letter/1889-02-26.

22 Letter from Gottfried Eschler, December 8, 1889, p. 2, The Wilford Woodruff Papers, wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/letter/1889-12-08.

23 Letter from Oliver Cowdery Dunford, September 30, 1889, pp. 1–2, The Wilford Woodruff Papers, wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/letter/1889-09-30.

24 He taught in Bear Lake County school districts for thirty years and managed an extensive family ranch. He also served in Church and civic leadership. See “Bear Lake County Mourns Loss of a Pioneer Citizen,” Paris Post, January 28, 1943, in “Oliver Cowdery Dunford,” geni.com, geni.com/people/Oliver-Dunford.

25 Letter from Charles Gledhill, August 20, 1889, p. 2, The Wilford Woodruff Papers, wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/letter/1889-08-20.

26 Letter from Alma Harris, December 27, 1889, p. 1, The Wilford Woodruff Papers, wilfordwoodruffpapers.org/letter/1889-12-27.

Rochelle HaleJuly 11, 2023

These are interesting accounts. I'd like to know more about the brother who said he would rather go to Scandinavia than prison. Some good friends of ours passed away several years ago, but the husband was one of the last married missionaries to be called (early 1950s) He ended up serving for three years and returned to a toddler son he had never met. When I was prompted to serve a mission, my family was not supportive. I told my bishop that I would have the funds if I worked just a few more months. He wanted me to submit my papers immediately and told me that generous ward members would help me. From the time I first thought about serving to my arrival in the mission field was about four months. Through the kindness of friends and wonderful miracles from the Lord, I came home with surplus funds that I returned to my bishop to help another missionary.