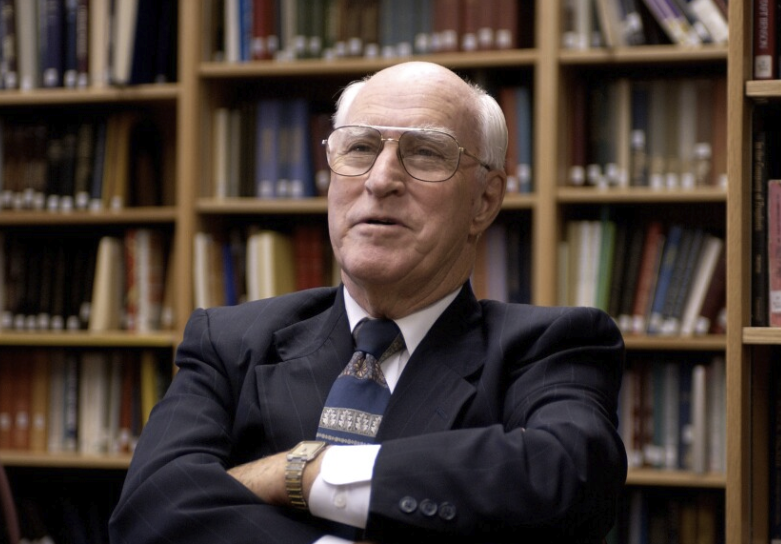

On July 9, 1944, a young Robert J. Matthews was sitting in his father’s home in Evanston, Wyoming, listening to a broadcast on KSL Radio. The speaker was Joseph Fielding Smith of the Quorum of the 12 Apostles. Robert said of that experience: “…he [Joseph Fielding Smith] quoted John 1:18, which says, ‘No man hath seen God at any time.’ And then Elder Smith said, Joseph Smith corrected that verse by revelation, and when he said revelation, that word penetrated right into my soul. It was the word revelation that did it. It struck me.”1

That singular event was the inspiration that led Dr. Matthews on an epic journey to becoming the premier LDS scholar of the manuscripts of Joseph Smith’s New Translation2 of the King James Version (KJV) of the Holy Bible. His efforts culminated in 1979 with the first edition of the KJV published by the Church of Jesus Christ of LatterDay Saints. The Church’s edition of the KJV included more than a third of the pertinent doctrinal verses from the New Translation either as footnotes or in an appendix. Before Dr. Matthews gained access to the manuscripts, no known Latter-Day Saint had seen them since they became the property of the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints3 (RLDS) in the late 1860’s.

Dr. Matthews personally compiled the New Translation entries for the LDS KJV. He used bits of paper with the verses typed on them and aligned them in their proper position for the 1979 LDS bible. It was during this cross-referencing project that the Church determined to call the entries the Joseph Smith Translation (JST).

In Fall 1944 Dr. Matthews entered BYU. His inspired interest in the New Translation took him to the offices of Dr. James R. Clark and Dr. Sidney B. Sperry. He asked Dr. Sperry “…if he knew that Joseph Smith translated the Bible. Dr. Sperry replied, ‘Yes, we know, but we don’t know much about it.’ So that was the beginning of my interest, and I never lost that feeling.”4

Dr. Clark’s response was essentially the same as Dr. Sperry’s. At that time the New Translation and the RLDS Inspired Version (IV) were relatively unknown to most LDS members. The IV was considered unreliable by LDS leaders because no one in the Church had been permitted access to the original manuscripts. Additionally, the use of any references from the IV was forbidden to be used in authorized LDS Church curriculum materials.

Dr. Matthews soon learned that if he was to understand the validity of the New Translation, he would need to obtain a copy of the IV as well as examine the original manuscripts. Unable to find a copy of the IV in any local bookstore, Dr. Matthews finally obtained a copy from N.B. Lundwall, a noted author of LDS books and incidentally, a convert himself from the RLDS Church.

From 1945 to 1950 Dr. Matthews compared each verse in the KJV with the IV, recording all the changes to the KJV in his copy of the bible. In 1953 Dr. Matthews wrote his first letter to the historian of the RLDS Church, Charles A. Davies, requesting permission to examine the New Translation manuscripts. He was told “No”.

On multiple occasions, over the next 15 years Dr. Matthews wrote to the RLDS Church historian seeking permission to examine the New Translation manuscripts. On several occasions he wrote the RLDS President W. Wallace Smith, a grandson of Joseph Smith. Each time his answer was “No”.

One day in the late 1960’s, the Deseret News published an article stating that the RLDS historian, Charles A. Davies, had passed away and that Richard P. Howard had been named as the RLDS historian. Encouraged to try Mr. Howard’s attitude, Dr. Matthews wrote him asking “If I came to Independence, would you show me the manuscript?” And he wrote back and said yes. I thought he didn’t understand, so I called him on the phone. He said, Yes, yes. You can come.”5

On June 20, 1968, Dr. Matthews was in Kansas City, Missouri as part of a three-week lecture tour for BYU Religious Education. Since Independence was nearby, he scheduled a visit to see Mr. Howard on that same day. He was permitted to examine the bible used for the New Translation, and view photocopies of the manuscripts. Mr. Howard was reluctant to allow Dr. Matthews to see or handle the originals of the manuscripts because they were “too precious.” Following his initial visit, Dr. Matthews made 12 other visits between 1968 and 1974, usually for a week each time. Initially he was allowed to transcribe the New Translation only from the photocopies.

As Howard’s trust increased, Dr. Matthews was granted complete access to the original manuscripts. Through the course of those visits he copied every word, every verse, every jot and tittle from the manuscripts. He also purchased a bible in which he copied every mark and notation found in Joseph’s bible. Finally, he had a complete transcription of the New Translation from Genesis to Revelation, as well as the physical description of both the manuscripts and Joseph’s bible.

The Latter-day Saint Church began their efforts to cross-reference all four of their canonized books of scripture in 1971. The three primary leaders of the committee to oversee the project were Thomas S. Monson, Chairman, Boyd K. Packer, and Bruce R. McConkie, all of the Quorum of the 12. They were aware of Dr. Matthews’ work on the New Translation manuscripts and watched it closely.

Sometime after Dr. Matthews completed his transcriptions in 1974, the committee to cross-reference the scriptures determined to include entries from the New Translation. Because of his relationship with RLDS personnel, Dr. Matthews was asked to obtain permission from the RLDS Church to include some New Translation entries in the LDS version of the bible.

Permission was granted and the work to determine which entries to include began in earnest. The decisions about what to include and what not to include were difficult. Those decisions were complicated by restrictions on space within the new Latter-day Saint version of the Bible. Miraculously as they were getting close to printing, a new thinner paper was found that significantly reduced the thickness of the bible while not allowing the ink to bleed through the pages. Thickness was a significant issue especially for the 4-in one scriptures the Church was printing.

Among the many miracles the program to cross-reference the scriptures experienced was the work of Dr. Matthews on what is now known as the Joseph Smith Translation. It goes without saying that Dr. Robert J. Matthews was raised up for this very purpose. It was the Lord’s inspiration and Dr. Matthews’ labor that opened the doors for the LDS Church to obtain copies of the manuscripts of the New Translation, thus topping off and completing the work of translation by Joseph Smith, Prophet, Seer, Revelator, and Translator.

—

The following links will take you to the 2-part Joseph Smith Papers TV series dealing with Dr. Matthews’ work:

Episode 20—The Joseph Smith Translation (JST), Part 1

Episode 21—The Joseph Smith Translation (JST), Part 2

In the coming months, I will publish articles addressing concepts we learn from the JST. Those who would like to follow along using the JST Red-Letter Editions may obtain copies at the link: The Joseph Smith Translation.

1. Ray L. Huntington and Brian M. Hauglid, “Robert J. Matthews and His Work with the Joseph Smith Translation,” Religious Educator 5, no. 2 (2004): 23–47; much of the information in this article comes from that interview which can be found online by selecting the following link: Robert J. Matthews and His Work with the Joseph Smith Translation | Religious Studies Center

2. This article uses three titles for the manuscripts and its publication. The New Translation was the title Joseph Smith, and the Saints used in referring to the work. The Inspired Version was a subtitle given the published work of the bible by the RLDS Church. The Joseph Smith Translation was the title given by the LDS Church for the 1979 LDS edition of the bible.

3. The RLDS Church is now known as the Community of Christ.

4. Ray L. Huntington and Brian M. Hauglid, “Robert J. Matthews and His Work with the Joseph Smith Translation,” Religious Educator 5, no. 2 (2004): 23–47.

5. Ibid.

For more reading on the Joseph Smith Translation, check out this Article by Scripture Central:

Why Did Joseph Smith Produce a New translation of the Bible?

Maryann TaylorAugust 7, 2025

Often, when I read the scriptures and something just feels "off," I look down and find a JST footnote that clarifies it all. I am so grateful for this profound blessing in elevating our understanding of the gospel, and applying it in our lives. I am grateful for the prophet, Joseph Smith and for those who worked to include these inspired verses our scriptures.

Gary LindnerAugust 7, 2025

I purchased a Kindle copy of the Red Letter Edition a few weeks ago and have been reading it instead of the KJV. I’ve almost finished the 4 gospels and feel the Spirit strongly when I read it. I also joy in the truths revealed by the corrections which are easier to appreciate in context with the original KJV.